In the 1970s, Gavin Bryars, along with such kindred spirits as Brian Eno, Philip Glass and Steve Reich, set the stage for contemporary composition. The first seeds of an international career were planted in Belgium, but the great recognition would come much later, with the unlikely hit "Jesus' Blood Never Failed Me Yet'.

Today, eighty years young, he recreates at the MSK the historic set he and his ensemble put on at the same venue 37 years ago and performs an anthology of his most iconic compositions at Ha Concerts.

An interview by Stijn Buyst

Before you turned to composing, you, along with guitarist Derek Bailey and drummer Tony Oxley, pretty much invented the European version of free jazz.

'Those two lived in Sheffield and at some point asked me to be the bass player for their regular Saturday afternoon gig. As an audition I had to play 'Moment's Notice' by John Coltrane, a very fast piece with two chord changes per measure. Completely insane, but somehow my playing convinced them.

We initially played harmonic jazz in the vein of Coltrane, Miles Davis and Eric Dolphy, but gradually we evolved into more experimental, freer playing. There were rumors circulating in the London jazz scene about guys somewhere against the Arctic Circle in the snow bringing something completely new. (chuckling) That was us, in Sheffield.

In the London jazz scene, rumours were reportedly circulating about guys bringing something completely new to the snow somewhere against the Arctic Circle. (chuckling) That was us, in Sheffield.

Gavin Bryars

Around the same time, here in Belgium, men like Fred van Hove and Cel Overberghe were going through a similar evolution.

'Yes, like Misha Mengelberg and Han Bennink in Holland and Peter Brötzmann in Germany.

Although I bid farewell to that music in 1966, I met all of those musicians by remaining friends with Derek.'

Why did you stop improvising so abruptly?

'I became interested in composition at that time, and more specifically in what John Cage, Morton Feldman and Earle Browne were doing. From Cage I remembered the idea of looking at music from a distance, and working more objectively, whereas our free improvisation was just very subjective.

I also felt that I could cross boundaries on my own that I couldn't overcome within that trio.

The concrete occasion came one evening in November 1966, when we had just played our third show of the weekend. A man came up to me and asked if he could play my bass for a while. Then he began maniacally going up and down the neck of the instrument: it all sounded fine, but I could sense from everything that he had no idea where he was taking the music.

Then I thought "If I worked so long for this, and he gets away with this, what's the point? That night I put my bass away not to touch it again for seventeen years. Kind of childish of me, maybe.'

That night I put my bass away not to touch it again for seventeen years. Kind of childish of me, maybe.'

Gavin Bryars

Your friend Brian Eno once told me that in the 1970s he didn't realize how small your world really was. He thought he knew a few members of the Fluxus movement, but after a while it dawned on him that there were no more members than the people he knew.

'That's really how it was. I myself worked with John Cage, Christian Wolff, Alvin Curran and Robert Ashley: that was a great community of kindred spirits, scattered across America and Europe. We were outsiders, not getting commissions from orchestras or grants. Helping each other created a powerful kinship, both practically and emotionally.

Also, when Steve Reich and Philip Glass first came to Europe in 1970, we all played in the same group. I remember Philip gave a concert at the Royal College of Art and the audience consisted of six people. Their music hasn't actually changed, but their status clearly has.'

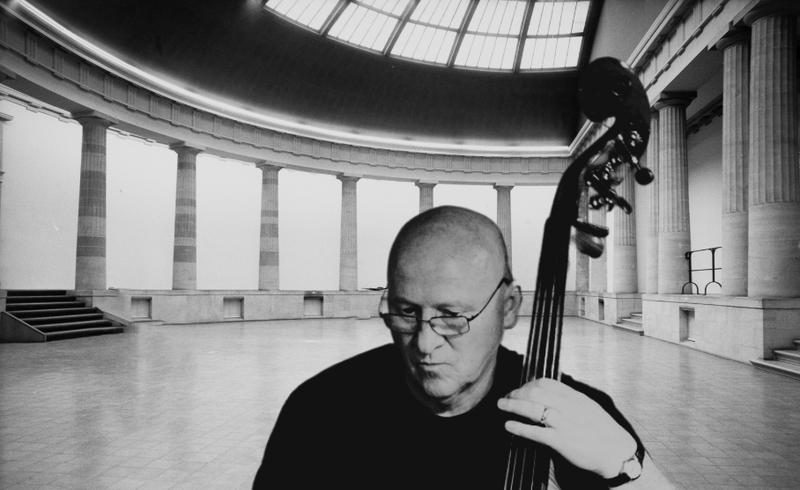

Did your past as a bassist still play a role in your later composed work, though?

'The bass is literally the root of everything. I still have two bass players in my ensemble. When my friend, the bassist Steve Swallow, saw a picture of my son with his first double bass, he said 'I hope he soon discovers the joy of playing a beautiful root note on the first note of the bar.' That's totally it...

When I played double bass a lot myself, I could recognize any bass player by ear, whether it was Richard Davis, Percy Heath, David Izenzon or Chuck Israels.'

The bass is literally the root of everything. (...) When I played double bass a lot myself, I could recognise any bass player by ear, whether it was Richard Davis, Percy Heath, David Izenzon or Chuck Israels.

Gavin Bryars

Your compositions are always conceptual in nature.

"I never start a piece without first delineating a concept.

Perhaps the best example is "The Sinking Of The Titanic," for which you did a lot of research.

'That piece came about very slowly. It began as a vague idea, in 1969, when I was still teaching at an art school. The idea was an imaginary score, where the audience had to imagine the music played by the orchestra as the Titanic sank.

But in 1972 someone asked me to do a version for orchestra, and so then I had to get to work. The story that the orchestra kept on playing - noble and insane at the same time - was known and proven even then: a radio operator reported about it from a sloop.

The idea I had for the piece was that the musicians also continued to play underwater. To do this, I first had to find out which hymn had been played, because testimony varied on this. People remembered a different hymn than the radio operator, when in fact it could be shown that at the time the ship sank they were already in a lifeboat miles away. So they remembered what they had been told later.

(chuckling) Now, I wasn't going to tell such an old berry who remembered the wrong hymn that she was a stupid old woman... The play also plays with that idea of distorted memories. So for the melodies, I relied on a combination of the hymn that was probably played and the hymn that some passengers remembered incorrectly.

I also researched the musicians, which was easy: the bass player turned out to have lived on the same street as I did.

The piece contains no piano because the orchestra couldn't get the piano on deck?

"I still figured out if the pianos could fit in the elevators, but by the time the ship was sinking, those elevators were no longer functional.

Sad for the pianist that he could not participate in that historic heroic moment, though.

'Well, they were two pianists. I should hope they ran for their lives. I haven't been able to find out if they survived, but if they made it at all they may have remained very quiet about it.'

Your most famous composition is probably "Jesus' Blood Never Failed Me Yet," which revolves entirely around a recording of a homeless person singing a mantra-esque, very vulnerable melody. That piece is improbably popular, any idea why?

'When I first recorded the piece in 1975, for Brian Eno's Obscure record label, very few people got to hear it, because there was little promotion. And those who did hear it generally thought it was rubbish.

But for some people who did hear the record - almost by accident - it became very important. Tom Waits told me, long before we worked together, that it was his favorite record ever.

By the way, one of the first performances of that play was in Belgium. For Europalia 1973, Hervé Thys of the Brussels Palace of Fine Arts had sent Godfried-Willem Raes (of Logos Foundation, sb) to England to see what was happening in the underground.

At that time, Belgium looked at music with a very open mind. I think the reason that the version we recorded in 1992 at Philip Glass' request became so popular is because the world had changed in the meantime: when I first recorded the piece, homeless people were still considered to be figures who more or less by their own choice stayed in the outskirts, but in the 1990s they had become ordinary family people with misfortunes: you and me. Although the fact that Tom Waits was singing along must have helped, too.'

Derek Bailey liked to tell how he was looked down upon as an improv musician, but that the simple mention that he had played on "Jesus' Blood" always got him free pints at the pub.

Yes, he loved it. It was completely different with the classical musicians I had to hire for the first recording: they came begging me afterwards not to be mentioned on the cover, it would be bad for their reputation.

With the 1992 recording it was the other way around: one guitarist kept calling me to make sure I spelled his name correctly.'

When you played at MSK in 1986, was that the first time you played as the Gavin Bryars Ensemble?

'That's right, we had already played together, but it was the first time we were announced as Gavin Bryars Ensemble. It's fair to say, by the way, that it's a very loyal ensemble, made up of outstanding musicians. With the guitarist, for example, I've been working together for thirty years.'

The program we will hear at the MSK on December 15 is almost identical to the performance you brought there in 1986, during the Off Off festival.

'We will bring modified versions of those pieces. In 1986, I had melodic percussion in the ensemble and I don't use those instruments now, to say the least. Most of those parts will now be played by the guitarist. The music will be mostly the same, but with a slightly different timbre.'

Eén stuk dat in 1986 in het programmaboekje stond, gaan jullie nu niet spelen.

‘Dat was ‘Englisak’, een adaptatie van een stuk voor twee zangers en vier piano’s, waarbij Alexander Balanescu de zangpartijen vertolkte op viool.

Maar we hebben dat stuk daarna nooit meer gebracht en het voelde logisch om het nu ook niet te brengen. Dat zou toch een beetje muzikale archeologie zijn, en weinig relevant voor mij.’

Ok, dankjewel voor het gesprek. Ik kijk uit naar de concerten.

‘Wel, ik ook. Ik ben nog altijd dankbaar voor de kansen die België me gegeven heeft vroeg in mijn carrière. Ik kijk er altijd naar uit om in Antwerpen, Gent, Brussel of Brugge te spelen.

Ik hou van jullie prettig gestoorde mentaliteit, levensvisie en jullie gevoel voor humor. En dan heb ik het nog niet over jullie fantastische eetcultuur gehad.

I am still grateful for the opportunities Belgium gave me early in my career. I always look forward to playing in Antwerp, Ghent, Brussels or Bruges.

Gavin Bryars

Gavin Bryars Ensemble: 'Iconics works'

With iconic work such as The Sinking of the Titanic and Jesus' Blood Never Failed Me Yet

20:15 Last tickets

Gavin Bryars Ensemble: '1986 revisited'

Re-enactment of a legendary evening

20:00 Tickets